To understand just how far psychiatrist Stuart Shipko will prostitute his professional reputation as a psychiatrist to pick up a paycheck as a paid expert witness from anyone willing to hire him as a forensic "mental expert," one needs not look much further than Shipko's embarrassing and dishonest work done on behalf of the defense in a trial involving convicted murderer Richard Glen Williams, 53, of Grass Valley, California.

|

Psychiatrist Dr. Stuart Shipko is a prostitute for hire

to anyone willing to pay him as an expert 'mental expert'

|

The crime took place in the home the estranged couple had once shared on the 10000 block of Alta Street in the sleepy small town of Grass Valley, not too far from the Sierra Nevada mountain range in Nevada County, California.

Hetty Williams was pronounced dead shortly after the shooting, while the accused, Richard Williams, slowly recovered from his self-inflicted abdominal and chest wounds during a month-long stay at Sutter Roseville Medical Center.

The case had generated so much negative local publicity and media attention that the venue of the murder trial had to be moved to Napa, California, to ensure a fair trial for Williams.

Needless to say, the defense hired disreputable psychiatrist, Dr. Stuart Lee Shipko of Pasadena, as their only expert witness, to oppose the prosecution's contentions that this was an open-and-shut case of cold-blooded premeditated murder by a jealous, enraged husband seeking revenge against his estranged wife in a murder and attempted suicide plot.

| |

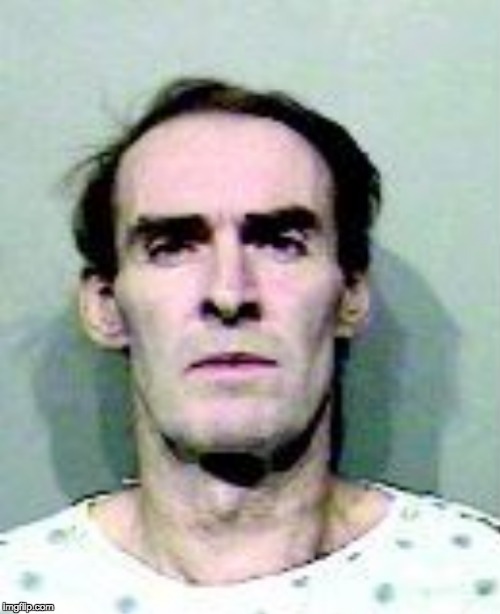

| Convicted killer, Richard William |

As revenge, Williams then planned an ambush of his wife inside the house, strangling her, and dragging her into the bedroom where he had stashed a loaded concrete nail gun.

After Williams did the unthinkable with the nail gun, police found a suicide note left by Williams on the bedside table that Williams had written an hour before Hetty Williams arrived at the house.

Thus, even an uninformed layman can see from the evidence that Williams had carefully planned out the entire murder-suicide plot well ahead of time, and this was no heat-of-the-moment impulse brought on by a fit of jealous rage, clouded by any psychiatric disturbances that affected William's state of mind.

|

| The victim Hetty Williams |

Shipko thus claimed that Williams was legally "unconscious" while he performed the killing, and therefore, was not guilty of committing the crime, despite the fact that Paxil, a mood stabilizer, is not commonly known to cause symptoms of psychosis, which is thought to be a thought disorder—a whole different realm of mental disorders compared to mood disorders.

To counter the defense's move, Deputy D.A. Katheryn Francis called on her own psychiatric expert witness, Dr. Eric Raimo of San Diego, an expert in alcohol and drug use disorders, to refute Dr. Shipko's less than honest testimony.

Needless to say, Dr. Raimo and Deputy D.A. Francis didn't have to do much to impeach Dr. Shipko's testimony because Shipko just wasn't a credible expert witness to begin with.

|

| Richard Williams in court for murdering his estranged wife |

"From our perspective, that's a little far-fetched," Nevada County D.A. Cliff Newell said of Dr. Shipko's outlandish explanation. "It seems [Williams] knew exactly what he was doing."

Newell pointed out that Williams testified under oath, describing each step of the killing from his own vivid recollections. Thus, Williams had to be conscious during the entire event; otherwise, how else could he remember what happened in such explicit detail if he was supposedly "unconscious?"

|

| Even the courts wanted to see Richard Williams in person before casting judgement on him |

Thus, Dr. Shipko failed to meet even the basic standard level of care as an evaluating physician on a subject/patient he gave expert testimony in court about.

According to court's own record: “Dr. Stuart Shipko formed his opinions in this case by reading police reports, reports by defendant’s psychiatrist and Dr. Roeder, a pyschologist, and by reading a transcript of defendant’s initial trial testimony, but he never met defendant.”

Thus, it was very easy for the prosecution to completely discredit Dr. Shipko's far-fetched psychiatric assessment of the Richard Williams because Shipko never even met Williams in person for an evaluation and forgot to tell the defense that someone who is "unconscious" shouldn't be able to recall every detail of the crime he committed.

|

| Richard Williams with his lawyer in court |

Based on failing to even examine the killer, Dr. Shipko floated an unfounded, and questionable theory of a drug-induced state of unconsciousness brought on by Paxil, according to court record in the appeals decision: “He [Shipko] described four mechanisms that can be caused by Paxil that equate to unconsciousness: Akathesia, or extreme restlessness, emotional blunting, delirium, and a serious sleep disorder.” (See p. 8, paragraph 2 of the appeal.)

Each of these arguments for a defense of unconsciousness during the murder was impeached by Dr. Shipko's own contradictory statements made under oath under cross examination or effectively rebutted by counsel's own expert witness, psychiatrist Dr. Eric Raimo, who pointed out Dr. Shipko's claims were not supported by current psychiatric thinking.

“On cross examination," the court record says, "Dr. Shipko conceded that goal-directed actions, such as searching on the internet for weapons, modifying the nails and drafting the suicide note, and clear subsequent memory, were inconsistent with delirium. ...He conceded that defendant had received written materials on the ‘Paxil withdrawl’ defense before he was seen by Dr. Roeder. And Dr. Shipko admitted he could not diagnose a patient without seeing him.” (See p. 8, paragraph 3 of the appeal.)

Dr. Raimo then systematically refuted the remainder of Dr. Shipko's dishonest claims made in court, according to the court record:

In his [Raimo’s] view, it was essential to interview a patient to rule out malingering. He testified Paxil does not cause unconsciousness. Further a person who is unconscious does not remember details of what he did, and is incapable of step-by-step planning. None of the four diagnoses posited by Dr. Shipko were supported by the materials Dr. Raimo reviewed: Two—akathisia and emotional blunting—are not forms of unconsciousness, and although delirium and severe sleep disorder can be forms of unconsciousness, they would not permit step-by-step planning. Mania can be goal-directed, but there was no sign of mania in the documentation or testimony Dr. Raimo reviewed. Defendant’s clear memory of events negated unconsciousness. Because defendant took Paxil successfully in 2004, it was unlikely he would have a severe reaction to it in the future. Paxil played no role in the killing and defendant was conscious. (See p. 9, paragraph 2 in the appeal.)

Akathisia merely relates to symptoms of agitation or restlessness brought on by a psychiatric drug, such as nervousness, pacing, repetitive limb motions (e.g., limb shaking or discomfort, etc.) or even anxiety, but doesn't have anything to do with a state of unconsciousness.

The court noted Dr. Raimo's accurate psychiatric assessment of the testimony given by Richard Willimas of his own state of mind during the time of the killing, "Dr. Raimo gave the opinion that a person who executes step-by-step planning and has a clear memory of events is a conscious person.” (See p. 11, paragraph 3 of the appeal.)

According to the FDA, the possible side-effects of Paxil include agitation, sensations of electrical zaps, nausea, vomiting, fevers, and changes of mood or suicidal thoughts or actions—mostly related to potential side effects of mood disturbances brought on by the drug—when the drug is first taken or when the dose is changed.

The court also noted that the defendant had successfully been on the drug in 2004; therefore, would not likely experience a severe adverse reaction to the drug later on.

“Because a person who can implement and recall a detailed plan is a conscious person, and because defendant was able to implement and recall a detailed plan," the court rightfully concluded, "therefore defendant was conscious when he killed Hetty.” (See p. 12, paragraph 12 of the appeal.)

“Defendant’s testimony showed he was able to execute a detailed killing plan and recall what he did later," the court went on to opine. "[I]t was defendant’s testimony about his actions and memory that undermined his claim of unconsciousness.” (See p. 15, paragraph 3 of the appeal.)

Thus, Dr. Shipko phoned in his expert opinion, and likely made up the "unconsciousness" defense out of thin air, against prevailing scientific and medical knowledge on the matter, because he prostituted his own integrity as a gun for hire; however, he was caught on his dishonesty in this case.

Dr. Shipko went well beyond his role as a psychiatric expert witness in determining that Richard Williams did not have the required mental state to commit murder. He was admonished in the court record in the final opinion when it said in no uncertain terms about his overreaching conclusions, “An expert may not testify as to whether the defendant had or did not have the required mental states, which include, but are not limited to, purpose, intent, knowledge, or malice aforethought, for the crimes charged. The question as to whether the defendant had or did not have the required mental states shall be decided by the trier of fact.” (See p. 12, paragraph 3 of the appeal.)

Apparently, being a forensic psychiatric expert can a lucrative business if you cater to your clients' every needs, but in the end where does that get you except a place where everyone knows you have no integrity to stand on?

Resources:

- The People of the State of CA v. Richard Glen Williams (11/19/2009) Court of Appeal of the State of CA, 3rd Appellate District, C057856, Super. Ct. No. SF05-0499, Nevada County, CA

- The People of the State of CA v. Richard Glen Williams (01/03/2008) Defendant's Sentencing Statement, Case No. CR137284, Superior Court of the State of CA, Napa County, CA

- "Nail gun murder: life in prison without parole," The Union (01/03/2008)

- The People of the State of CA v. Richard Glen Williams (01/02/2008) Victim impact statements

- "Guilty verdict in nail gun killing: 'I'm thankful that he will have a cinderblock tomb,'" The Union (11/20/2007)

- "Murder verdict in nail gun case," Napa Valley Register (11/20/2007)

- "Jury convicts Grass Valley man for slaying wife with nail gun," San Diego Union Tribune(11/20/2007)

- "Nail gun suspect's fate in jury's hands: Accused wife killer 'not a homicidal maniac,' lawyer says," The Union (11/16/2007)

- "Psychiatrists testify in nail gun murder: Defense says Williams didn't know what he was doing," The Union (11/15/2007)

- "'He shot her, reloaded, then shot her again': Prosecutor picks up nail gun in dramatic opening murder trial," The Union (11/03/2007)

- "Murderer to testify in nail-gun case, Deputy DA: Men shared a jail cell at Wayne Brown," The Union (07/18/2007)

- "Motions delay nail-gun trial: Defense asks that suspect's jail mates not testify," The Union (08/30/2007)

- "Victim felt no fear, according to witness," The Union (01/18/2006)

- "Nail-gun murder suspect out of hospital," Tahoe Daily Tribune (11/28/2005)

No comments:

Post a Comment